Black History figures everyone should know about

For too many years, history books have focused on the achievement of White Americans, while many of the inspiring contributions of African Americans, and others, have been overlooked. From Black inventors, comedians and doctors to astronauts and entrepreneurs, the achievement of these Black History figures paved the way for all who followed in their footsteps. If you’re looking for Black History Month activities to participate in, learning the names of these amazing trailblazers is a good place to start. Then, read up on these Black History Month facts and support these Black-owned businesses.

Rebecca Lee Crumpler

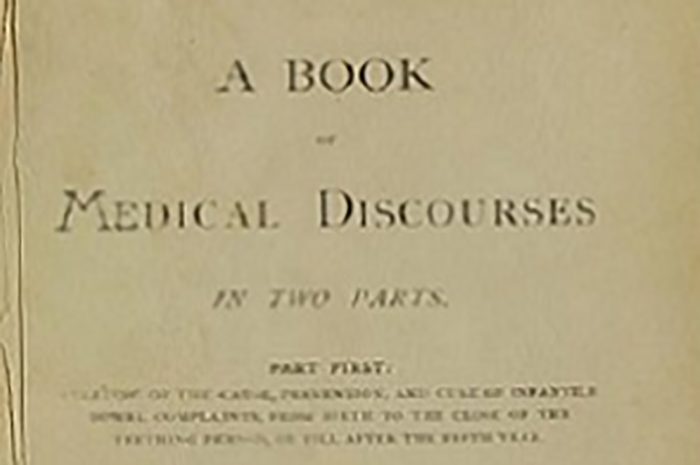

More people should know the name Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831–1895). Crumpler was the first Black American woman physician. She became a doctor of medicine at New England Female Medical College in 1864, just a year before the end of the Civil War. She spent her career focusing on the care of women, children and people of color who were unable to pay for medical services, fighting racism and sexism every step of the way.

In 1883, she published a book called A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts, which many historians believe to be the first medical text by a Black American writer. You might not have heard her name until now, but spread it far and wide, because Crumpler is one of the pioneering women who changed the world—and one of the most inspiring Black History figures.

Mary McLeod Bethune

Both of Mary McLeod Bethune’s (1875–1955) parents were formerly enslaved. Despite this, Bethune became one of the most important and inspiring leaders in education, women’s rights and civil rights. As one of 17 children, she grew up picking cotton alongside her family. She eventually went to boarding school and became a teacher. She married another teacher, and the pair moved to Florida, where Bethune opened a boarding school of her own, The Industrial School for Training Negro Girls. The school eventually merged with an all-male school and became Bethune Cookman College in 1929.

Bethune didn’t stop there. She was a champion of women’s rights, worked in President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration as the Director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration and served as vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Her tireless efforts helped ensure she left behind a better world than the one she was born into. You’ll also love these heartwarming stories of teachers who changed lives.

Margaret Strickland Collins

It was obvious from a very young age that Margaret Strickland Collins (1922–1996) was brilliant and motivated. She grew up in Institute, West Virginia, a community largely comprised of Black intellectuals, skipping two grades to graduate high school at the age of 14. She promptly started college, earning a degree in biology. She went on to study entomology and earn her PhD at the University of Chicago.

Collins spent much of her career studying termites as a research fellow for the Smithsonian Institute, which now houses a collection devoted to her work. She was also a Civil Rights activist, becoming one of the many ordinary people who changed the world when she stepped up to drive people back and forth to work during the Tallahassee bus boycott.

Benjamin Banneker

Benjamin Banneker’s (1731–1806) father was formerly enslaved, and his mother was a former indentured servant, though Banneker himself was born free. He was self-educated, but his lack of formal education didn’t hold him back. Banneker became a surveyor, astronomer and, most notably, a writer of almanacs.

In those almanacs, Banneker included personal writings, tidal information, medical information, astronomical calculations and information on insects like bees and locusts. He was also an outspoken abolitionist who exchanged letters with Thomas Jefferson, U.S. secretary of state at the time. Find out why Black History Month should be celebrated all year long.

Elizabeth Freeman

Less than a year after Massachusetts adopted its state constitution, a woman no one had heard of did an extraordinary thing. Originally born Mum Bett, Elizabeth Freeman (1744–1829) was enslaved, but she filed a legal challenge, citing the constitution’s promise of liberty—and won her freedom in court. She became the first woman to successfully file a lawsuit for her right to freedom in the state of Massachusetts.

This groundbreaking moment established a pathway for a host of subsequent suits and eventually prompted the Massachusetts Judicial Court to outlaw slavery altogether. After earning her freedom, Bett changed her name to Elizabeth Freeman and worked as a paid domestic worker, midwife, healer and nurse. Her efforts paid off and she was eventually able to buy her own home. Read (and share) these inspirational Black History Month quotes.

Mae Jemison

For every famous woman in flight, there are sadly countless others whose names are not nearly as well known. Among them is Mae Jemison (1956–present). Jemison became the first Black woman in space in 1992, as an astronaut on the second launch of the Space Shuttle Endeavor. This achievement is even more admirable when you consider that she was afraid of heights.

Jemison was successful at an early age, starting Stanford University when she was just 16 years old. In 1981 she earned her Doctorate of Medicine from Cornell University. Afterward, she served two years in the Peace Corps. She established a private practice and subsequently joined NASA upon her return. And if that wasn’t cool enough? She also accepted an offer to guest star on Star Trek: The Next Generation, particularly meaningful because the original series was a favorite of hers as a child.

George Carruthers

When people think of NASA, they usually think of astronauts, or spending a day inside the International Space Station. But many of the heroes of NASA never leave the ground. One such person is physicist George Carruthers (1939–2020). Carruthers built his own telescope when he was 10 years old and started working at U.S. Naval Research Library as a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow after earning a PhD from the University of Illinois.

In 1969, he was awarded a patent for an ultraviolet camera; it was used in 1972 during the first moonwalk of Apollo 16, allowing scientists to analyze the atmosphere in more detail than ever before. In later years he continued to develop inventions for the NASA program and paid it forward by developing an apprenticeship program that gave high school students the chance to work in the U.S. Naval Laboratory. In 2003, he was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Here are the most famous inventions from every state.

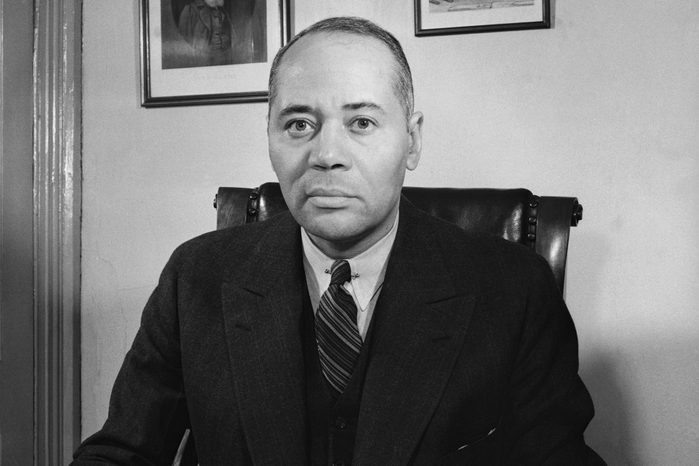

Ralph Bunche

Many people believe that Martin Luther King Jr. was the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize, but that’s not the case. That honor goes to Ralph Bunche (1904–1971), a name that is tragically under-recognized.

Bunche was valedictorian of his class in both high school and college and went on to earn a doctorate in political science at Harvard University. He was a key participant in drafting and adopting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights alongside Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1947, his work with the United Nations led to a role on a team tasked with alleviating the Arab-Israeli conflict in Palestine. It was for this work that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950.

Later in life, he worked to promote Civil Rights in the United States, participating in historic events like the March on Washington and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Mark Dean

If you’re reading this on a personal computing device, you’ve got Mark Dean (1957–present) to thank. The scientist and inventor was a trailblazer in the field of computing. Dean discovered he had a knack for working with his hands from a young age, once helping his father assemble a tractor from scratch. He studied engineering in college and started working with IBM soon after earning his degree.

At IBM, Dean quickly moved up the ranks, developing three of the company’s nine original patents. Among his projects were the first color computer monitor and the first gigahertz chip, which performs a billion calculations a second. Learn what computers looked like the decade you were born.

Madam C.J. Walker

Madam C.J. Walker (1867–1919) was raised in poverty but went on to become one of the wealthiest and most influential women of her era. She was born Sarah Breedlove to sharecropper parents who had both been previously enslaved. One of her first steps on her way to success was finding work as a sales agent for a product formulated to restore hair growth, of particular importance to Walker because she was experiencing hair loss herself.

Eventually, she took $1.25 and used it to found her own hair-care line, focusing on products for African American hair. She believed Black women should be financially independent and provided training and sales jobs for more than 40,000 African American individuals. She eventually became a millionaire and paid it forward with contributions to the YMCA, scholarships for African American students, the NAACP and more. When she died, it was revealed that she’d left two-thirds of her future profits to various charities. Don’t miss these other famous female firsts.

William H. Carney

It’s no secret that the contributions of Black soldiers in the Civil War have been shamefully overlooked, which is why it isn’t surprising that many people haven’t heard of William H. Carney (1840–1908), the first Black soldier to win the Medal of Honor. Born enslaved, Carney was a fighter from an early age, escaping as a young man and finding his way to freedom through the Underground Railroad. Although he originally felt called to become a minister, when he learned troops comprised of Black soldiers were forming to fight in the Civil War, he felt compelled to join.

Carney was promoted to sergeant and awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroic actions in the 1863 Battle of Fort Wagner, in which he made sure his regiment’s flag never reached the ground despite being shot four times. Find out the answers to these American history questions almost everyone gets wrong.

Moms Mabley

Comedy is a notoriously difficult field to break into, a fact only amplified if you happened to be a woman, let alone a Black woman, in the early days of standup and vaudeville. But that didn’t stop Moms Mabley (1894–1975).

She was born Loretta Aiken and suffered the premature deaths of both her parents at a young age. She was impregnated twice though the violence of rape and gave birth to children who were taken away. At 14, she joined the African American Vaudeville Circuit. She went on to be the first woman featured on stage at the prestigious Apollo Theater and was invited back so many times she appeared more than any other performer. She had featured roles in movies, recorded gold comedy albums and appeared on television shows like The Smothers Brothers and Ed Sullivan.

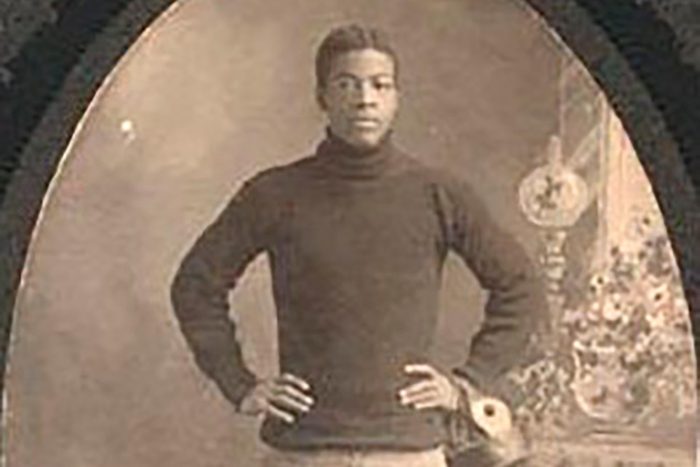

Charles Follis

NFL fans today might have a difficult time imagining an era when football wasn’t integrated, but that was the case until Charles Follis (1879–1910) became the first Black American professional football player. Follis was a gifted athlete who played football in high school and joined an amateur league in college. In 1904, he signed on with the Shelby Athletic Club in Ohio to become the first Black professional football player.

Opposing players frequently went out of their way to injure him with excessively rough play, and he was subjected to taunts and racial slurs by the fans of other teams. After an injury ended his football career, he joined the Cuban Giants, a Black baseball team. He died of pneumonia at the age of 31. Read on to find out why Black History Month is more important than ever.

Jane Bolin

Jane Bolin (1908–2007) stood apart from the crowd at an early age. A brilliant student, she graduated from Wellesley College in 1928, despite experiencing racism and isolation from her classmates. She went on to be the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School, and at age 31 she became the first Black woman in the country to be sworn in as a judge. She retired from the bench at age 70 and focused on volunteer work for local schools. If you want to follow in her footsteps, start with these creative ways to volunteer and make a difference.

Matthew Henson

Expeditions tried to reach the North Pole for 18 years but were always unsuccessful due to the brutal cold and untamed conditions, until Navy Lt. Robert Peary led the first expedition to finally reach the North Pole. By his side was Matthew Henson (1866–1955), an African American explorer born to free sharecroppers.

Peary learned the Inuit language of the natives in the area, which proved key to the explorers’ success. In addition, he mastered several Intuit survival techniques and had superior dog-sledding and navigational skills. In 1912, Henson published a book about his adventures, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, and went on to receive a Congressional medal and a Presidential Citation in 1950. Looking at these majestic photos of the real-life North Pole, it may be hard to imagine a time when the area was undocumented and unexplored.

Mary Ellen Pleasant

No one is sure if Mary Ellen Pleasant (1815–1904) was born free or into slavery, but her adult years are well documented. Pleasant was a brilliant and creative entrepreneur, and despite the barriers in place for African Americans and women in general, she managed to become one of the first female African American self-made millionaires in our nation’s history.

She moved to California during the Gold Rush and found employment as a domestic worker, where she was generally disregarded and treated by her employers as if she were invisible. She used this to her advantage, listening in on their conversations and gathering tips on stocks and investments in real estate and gold and silver mines. She eventually bought several boarding houses and laundry businesses and often disguised herself as a menial worker in order to continue to have access to hot tips.

She used some of her fortunes to support the Underground Railroad and abolitionist causes. Unfortunately, she fell victim to vicious rumors and unscrupulous business partners, and ultimately, she died in poverty.

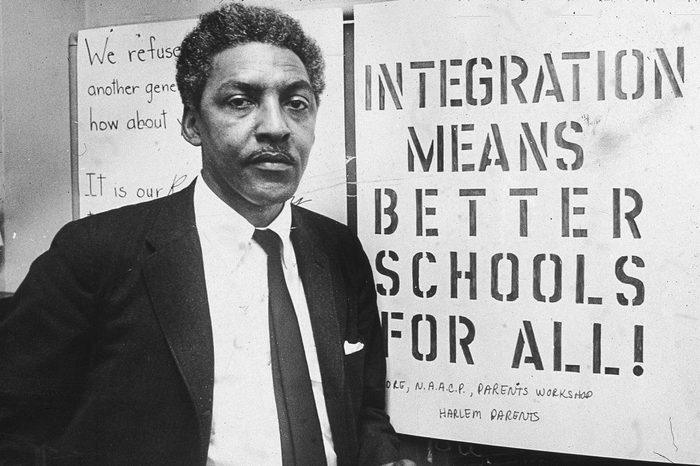

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin (1912–1987) was gay and African American, which meant he faced discrimination on multiple levels. Nevertheless, he contributed greatly to forward progress and the cause of equality in the country. Rustin was one of the key organizers for the March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his history-making “I Have a Dream” speech. Rustin’s work went largely unrecognized at the time, but in 2013 he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by then-president Barack Obama for his work. He’s one of the amazing LGBTQ+ heroes you didn’t learn about in history class.

Ursula Burns

Ursula Burns (1958–present) became one of the women CEOs who made history when she was named CEO of the Xerox Corporation in 2007, making her the first African American woman to hold such a position in Fortune 500 company. Her creative and out-of-the-box leadership helped change the company from a mediocre performer focused on copy machines and yesterday’s hardware to a globally competitive high-tech company focused on innovating software and cloud technology.

Robert Sengstacke Abbott

Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1870–1940) was the founder of the Chicago Defender, in 1905. It started as a four-page paper printed with almost entirely borrowed money. At first, Abbott acted as photographer, editor and reporter, but he slowly began to attract volunteers willing to share the workload as the paper expanded.

The Chicago Defender reported on issues important to the Black community, including riots and lynchings, and encouraged African Americans living under the Jim Crow laws of the South to make their way north. Many credit the Chicago Defender with paving the way for other prominent Black-focused publications, such as Ebony and Essence.

Claudette Colvin

Rosa Parks is famous for launching the Montgomery Bus Boycott when she refused to give up her seat and move to the back of the bus for a White passenger. But before Parks, there was Claudette Colvin (1935–present). Colvin was just 15 years old when she refused to give up her seat for a White passenger, nine months before Parks did the same thing. The schoolgirl was handcuffed, arrested and thrown in jail. She subsequently participated in a court case that outlawed bus segregation in Montgomery and Alabama.

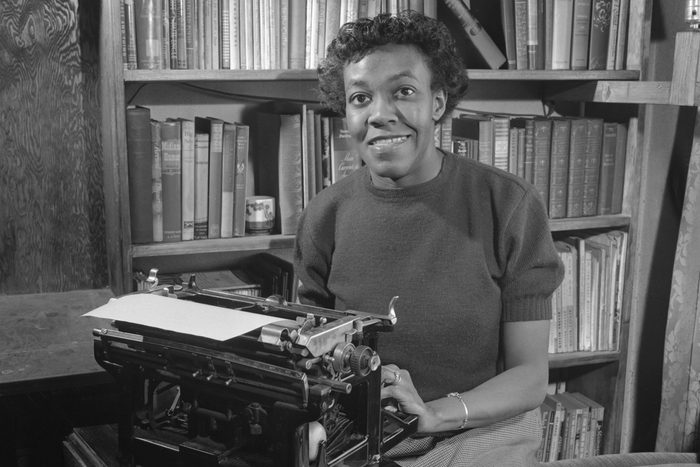

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000) was a groundbreaking African American poet. For the most part, she didn’t write about flowery subjects; instead, her prose shined a light on the Civil Rights Movement and the poor economic conditions forced on many Black Americans.

She was the first Black writer to be awarded the prestigious Pulitzer Prize and the first Black woman to serve in the role of Poetry Consultant for the Library of Congress. She was a fierce advocate for other poets, often visiting schools to teach workshops, and despite being far from wealthy she selflessly used her own money to establish prizes to support the poetry community. Check out these books by Black authors you’ll want to know about.

Alice Coachman

There are many Olympic moments that changed history, and one of the most important is when Alice Coachman (1923–2014) became the first Black woman in the world to win a gold medal in the 1948 Summer Olympics in England. King George VI personally presented her with her winning medal, and her hometown of Albany, Georgia, threw a parade in her honor when she returned home. Still, racism marred that happy day, when the event was segregated and the mayor refused to shake her hand. Coachman went on to become a teacher and established a foundation to give back to those in need.

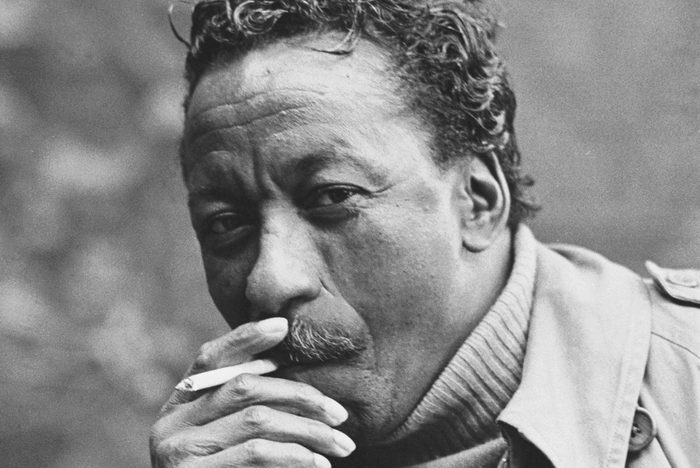

Gordon Parks

If you’re a fan of arrestingly beautiful photos that stand the test of time, you’ll want to check out the work of photographer Gordon Parks (1912–2006). Parks took some of the most iconic photos of his generation for publications like Life magazine, Time and Ebony. When he directed the movie Shaft, he became the first African American to direct a major motion picture. Parks always felt he was doing something more important than just taking photos—he was using his camera to change hearts and minds by documenting the injustices of his time. He famously said that he used his camera to fight against poverty, racism and social wrongs.

Mildred Jeter Loving

It may be hard to believe, but interracial marriage was once a crime punishable by law. In 1958, Mildred Jeter (1939–2008), who was of African American and Native American descent, married Richard Loving, a White man. The newlyweds were told they would face prison time if they didn’t leave the state of Virginia. They left their home, and she gave birth to three children, however they longed to return to their home state.

Mildred Loving wrote a letter to attorney general Robert Kennedy, who connected her with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The Lovings’ case eventually landed with the U.S. Supreme Court, which unanimously ruled that laws barring interracial marriage were unconstitutional. At last, the Lovings could return home, and more important, they opened the door for other couples to marry the person they loved regardless of skin color.

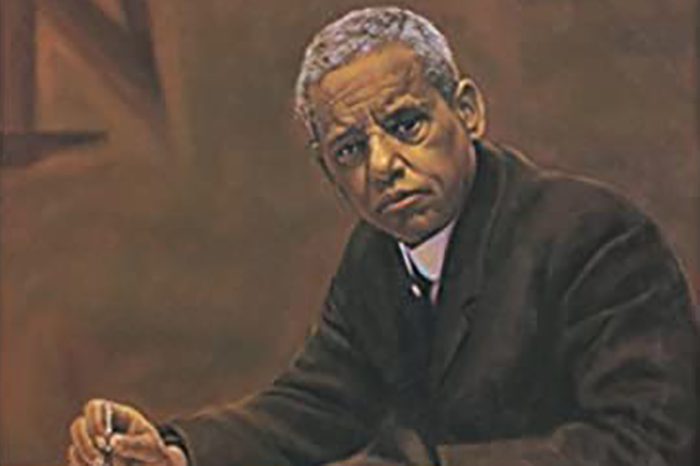

Charles Hamilton Houston

Charles Hamilton Houston (1895–1950) was a Black attorney who worked tirelessly to fight for civil rights and overturn the bigoted laws of Jim Crow. He was part of nearly every Supreme Court case concerning civil rights during his era, including the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education, and he became known as “the man who killed Jim Crow.” In honor of Houston’s tireless work to make our country a fair place for every citizen, regardless of color, Howard University (where Houston once taught) named a hall for him and Harvard Law named an institute and a professorship after him. These essential books for understanding race relations in America are must-reads.

Ethel Waters

Ethel Waters (1896–1977) was an influential Vaudeville performer who went on to have a stellar career on Broadway. She was also a Grammy-winning recording artist whose vocal style was oft-imitated by her contemporaries. She also starred in movies and was nominated for an Academy Award for Pinky in 1942.

In 1950, Waters became the first Black American to lead a television program, and she was the first Black actor to win an Emmy Award. Later in life, she toured with Billy Graham, using her musical talents to sing in his Crusade.

Moneta Sleet

One of the most iconic photographs of the civil rights era is a picture of Coretta Scott King cradling her daughter with a veil over her face at her husband, Martin Luther King Jr.’s, funeral. The photographer who captured that image was Moneta Sleet (1926–1996), who won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo, making him the first African American man to do so. But it almost didn’t happen. Black photographers were barred from the event until Scott King insisted they be represented.

Bessie Coleman

When people think of early female pilots, they usually think of theories about Amelia Earhart, but they’re missing out. A little-known pilot named Bessie Coleman (1892–1926) is equally compelling. Coleman worked as a manicurist but dreamed of becoming a pilot. Unfortunately, no flight schools would admit her because she was female and of African American and Native American descent.

Rather than give up, she enrolled in French classes so she could apply for training in France, where no such restrictions existed. She received her license and became the first Black woman to fly in a public exhibition, in 1922. She became famous for her daring stunts and traveled the world, refusing to appear anywhere the audience would be segregated. Sadly, she was killed in a flight accident in 1926.

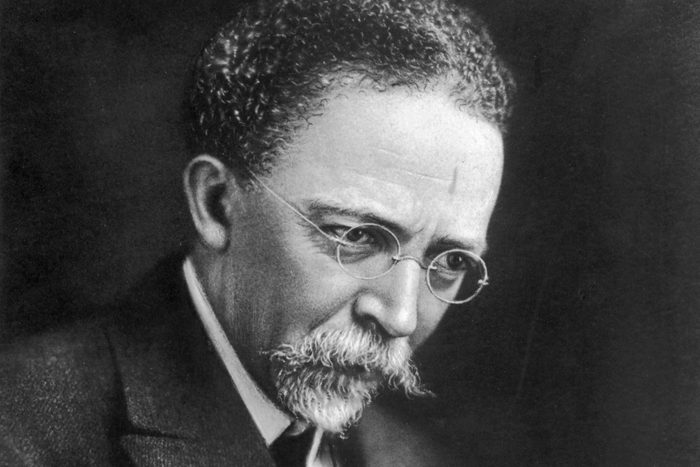

Lewis Latimer

There are perhaps no inventors in American history as well known as Alexander Graham Bell and Thomas Edison, but a lesser-known inventor took a key role in helping them invent the telephone and the lightbulb. Lewis Latimer (1848–1928) was a brilliant young Black man who taught himself drafting while working in a law patent office. His talent was noticed, and he was promoted to draftsman. He subsequently worked on several of his own inventions, including an air conditioner. He eventually helped patent the telephone for Bell and worked with Edison on the light bulb.

Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) was the first African American painter to find worldwide fame, during the 1800s. He was the son of a minister, and as such, most of his work centered around scenes inspired by the stories of the bible. He married a White American opera singer he met in Paris, and the pair eventually moved to France permanently to escape the racism of the United States. Still, his paintings received continuous acclaim and awards in the United States, and today many of them can be found in the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Beverly Loraine Greene

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915–1957) is thought to be the first female architect in the United States, a feat that is that much more impressive, given the fact that she was African American and faced discrimination for both her skin color and her gender throughout her career. She worked on a number of notable projects, including the United Nations headquarters in Paris, the arts complex at Sarah Lawrence College and buildings at New York University. Her funeral was held at Unity Funeral Home in New York City, another building she helped design.

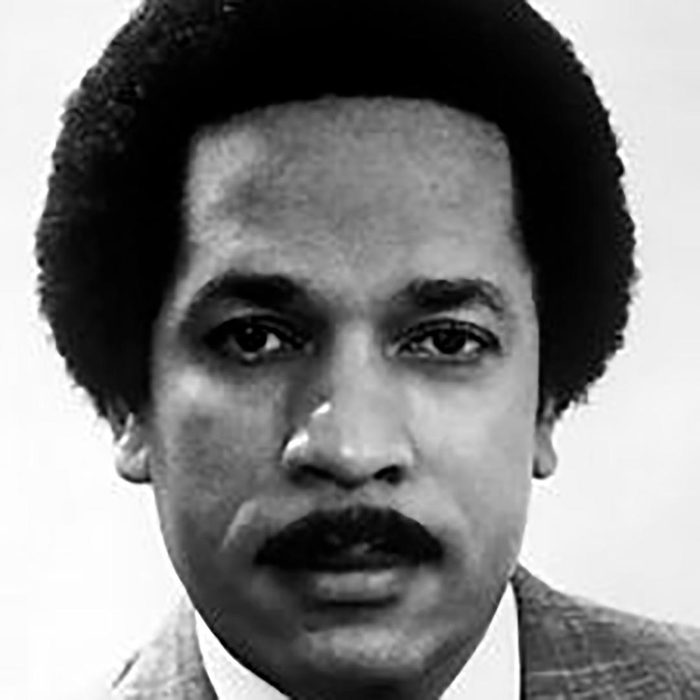

Max Robinson

Max Robinson (1939–1988) was the founder of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) and co-anchored ABC World News Tonight, which made him the first African American news anchor for a broadcast network. Throughout his career, he was vocal about racism and the need to create more opportunities for Black journalists, even at his own network.

He died of complications from AIDS and kept his diagnosis hidden to avoid facing the stigma associated with the disease at the time. However, he asked his wife to go public with his cause of death before he passed in an effort to raise awareness and educate the Black community about the seriousness of AIDS.

Henry Johnson

Henry Johnson (1892–1929) was a member of the first African American unit in the United States to serve the country in battle during World War I. In 1918, he fought heroically in hand-to-hand combat, killing a German soldier and rescuing a fellow wounded American soldier in the process. He received more than 21 wounds, but his discharge paperwork didn’t mention them, which meant he was denied the Purple Heart and disability pension he so rightfully deserved.

Since Johnson was poor and illiterate, he was at a loss for how to correct the issue. He died, destitute, at the age of 32. Eventually, Johnson’s contribution and shocking oversight were uncovered and President Bill Clinton awarded him with a posthumous Purple Heart in 1996; the army later awarded him their second-highest honor, the Distinguished Service Cross, in 2001. In 2015, he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by then-president Barack Obama.

Georgia Ann Robinson

Georgia Ann Robinson (1879–1961) was one of the first Black American women to be appointed as a police officer in the United States. A former governess, Robinson was a suffragette who worked tirelessly to make the world a better place for women and people of color. During World War I, there was a shortage of men, and she was recruited to work as a police officer in Los Angeles. Though she initially worked on a volunteer basis, three years later she was promoted to the rank of full-time officer. She retired after being hurt on the job but continued her volunteer work with the community.

Mamie Johnson

Baseball might be America’s pastime, but there was a time when the sport was unjustly segregated and Black players were relegated to a separate league. The Negro League was not only open to people of color, but it was also open to women, and Mamie Johnson (1935–2017) was one of three women to play right alongside the men—and the only woman to serve as a pitcher.

They nicknamed her Peanut, for her small stature. After retiring from baseball, she went to work as a nurse—but she still loved educating people about the Negro League and her beloved sport of baseball.