The first-ever dictionary

The earliest single-language dictionary in the English language was known as the “Table Alphabeticall.” Produced by a man named Robert Cawdrey in 1604, it contained around 3,000 words. It didn’t give “definitions” so much as synonyms; the author’s purpose, he wrote, was to introduce more complicated words to “ladies, gentlewomen, or any other unskillful persons,” so they could better understand scriptures and sermons. This is how new words get added to the dictionary.

The word with the most meanings

You might be surprised to learn what the most “complicated” word in English is—that is, the word with the largest number of separate definitions. And, well, there actually are a couple of answers. The current winner is technically “set,” and it’s held the title since 1989. In that edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, the word had…wait for it…430 separate definitions. But in the next (print) edition of the OED, due out in 2037, there will be a new most complicated word in English, and a new champ. According to the editors, the word “run” has now amassed 645 separate meanings…for the verb form alone! It’s amazing to think that a three-letter word can carry so much meaning.

The longest word… is a joke

Move over, antidisestablishmentarianism! The longest English word that generally appears in dictionaries is “pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis,” the name of a lung disease. It has forty-five letters. According to Lexico, this word was actually created to poke fun at long, overly technical medical terms. But the mastermind behind the word hadn’t seen anything yet. Another, much longer word is actually considered the longest in English with 189,819 letters—and it’s another scientific term. It’s the name for a protein nicknamed “titin.” It would take a full 12 pages to write each letter out, so, understandably, dictionaries choose to omit it.

Less-long longest words

Yes, the 28-letter “antidisestablishmentarianism” does get a title of its own. It’s considered the longest “non-coined, non-technical” word in most dictionaries. Admittedly, it’s not in common usage today, as it was created to refer to the Church of England in the 19th century. But another word deserves a shout-out. According to Grammarly, “incomprehensibilities,” at 21 letters, has been named the longest word “in common usage.” Turn your curious brain to learning these facts about every single letter of the alphabet—though you might not have room in your memory for all of “antidisestablishmentarianism”.

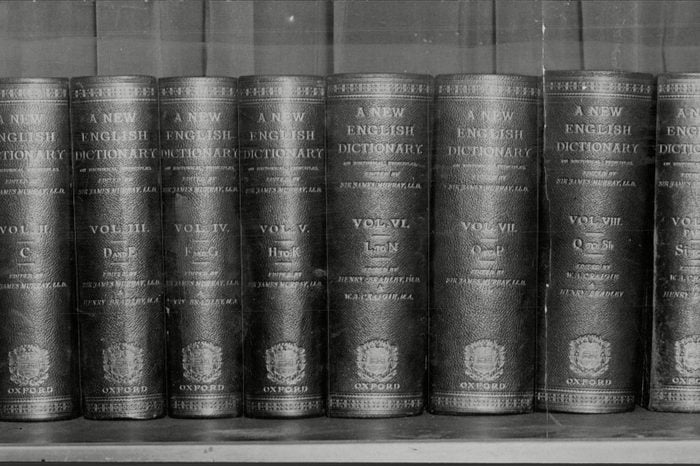

A murderer was a contributor to the first Oxford English Dictionary

This is one of the quirkier tales about the creation of the dictionary! William Chester Minor was a Civil War veteran suffering from serious paranoid schizophrenia after experiencing the horrors of war. Specifically, he was having repeated nightmares that there was an intruder in his room. One night in 1872, Minor shot at what he was sure was an intruder—it turned out to be an innocent passerby, and Minor had killed him. Minor confessed to the murder, explained what made him do it, and was committed to the Broadmoor Insane Asylum.

While imprisoned at the asylum, Minor started contributing to the Oxford English Dictionary’s “mail-in volunteer system,” sending in words to the dictionary’s editor, James Murray. Murray found that Minor (whom he did not know was in an asylum!) was one of the most prolific and by far one of the most valuable contributors. The two men would eventually meet almost 20 years after the start of their correspondence.

Lots of new words are added every year

At the end of every year, you’ll probably see a few lists of the funniest, most surprising, most slang-y words that were added to the dictionary that year. But such lists contain only a hand-picked few of upward of 1,000 added to the dictionary every year! In 2020, for instance, Merriam-Webster added 550 words during the first cycle in April, and will announce even more during the second cycle. Of course, such additions are offset by dictionary words that go extinct, for better or worse.

The dictionary included a “fake” word for five years…

Dictionary editors are only human, so they do make mistakes! Perhaps the most famous dictionary error of all time is “dord,”. While editors were compiling words for the 1934 Webster’s New International Dictionary, a card for an abbreviation accidentally ended up in the pile of word cards. (The plan had been to keep abbreviations and words separate.) The abbreviation was “D or d,” a capital or lowercase D short for “density.” But since it ended up in the word pile, it was printed in the dictionary as “Dord,” meaning “density.” But no harm done; no one noticed the error for five years!

… and was missing a “real” word for 50

If it seems like it’d be virtually impossible for dictionary editors to remember every single solitary word, you are correct. When the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary debuted, in 1888, it was missing the word “bondmaid”. An old-fashioned (even then) term for an enslaved girl, “bondmaid” had been in common use in the 16th century and was derived from a Biblical translation. You might find it remarkable that it took until the 1933 edition for the word “bondmaid” to finally appear, until you learn that it actually took 50 years for the second edition to come out.

Poems complicate things

In addition to the famous “dord,” there are quite a few other fake words that have ended up in the dictionary. A couple of these were derived from poems. One such word, which appeared in Richard Paul Jodrell’s Philology on the English Language in 1820, was “phantomnation.” While it sounds like the loyal fan base of some sort of ghost creature, it’s actually a word that comes from the epic poem The Odyssey. Odysseus travels to the Underworld and makes offerings to “the phantom-nations of the dead.” Another “word,” “redripening,” came from a poem by Richard Savage. (It was actually “red-ripening,” describing strawberries.) Jodrell included that one in his compilation too. Those rotten poets; how dare they be creative with their use of language!

Speaking of poems…

Children’s poet Shel Silverstein wrote a poem, called “Memorizin’ Mo,” about a guy who memorized the dictionary. (We’re unaware of anyone who’s accomplished this feat in real life.) It appeared in his 1981 poem collection A Light in the Attic. Unlike the dictionary, the poem is very brief. The full poem reads:

“Mo memorized the dictionary

But just can’t seem to find a job

Or anyone who wants to marry

Someone who memorized the dictionary.”

Yup, it’s a bit of a downer! Marriageability aside, here at RD.com we’d find someone who’d memorized the dictionary to be a dream job candidate! In the meantime, maybe one of these funny errors in famous works of literature will cheer you up.

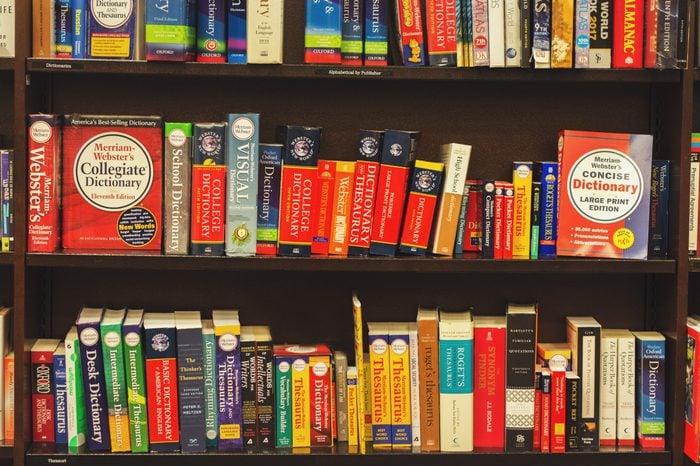

Amazon’s best-selling dictionary

Merriam-Webster has pretty much cornered the market on Amazon dictionary sales! The best-selling dictionary on the site is Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary. The second-best seller is Merriam-Webster’s Pocket Dictionary, and their The Complete Rhyming Dictionary is third. The American Dictionary of the English Language sneaks into the fourth spot, but Merriam-Webster products have the fifth and seventh spot too (as of press date; Amazon’s page updates hourly.)

The most misused word?

Of all the words that have been mixed up with other words and had their meanings diluted over time, dictionary.com has declared one the most abused of all. Any guesses? It’s “ironic.” Their argument is that the word is almost never used correctly—you’ll most often hear it used to mean something that’s funny, coincidental, or unexpected. And while it can describe something that is any of those adjectives, it has to be funny, unexpected, etc. because it’s the exact opposite of what you’d expect. So it’s a much more nuanced word than its popularity would suggest—yet there are still plenty of funny true examples of irony that give you a good idea of what it really means.

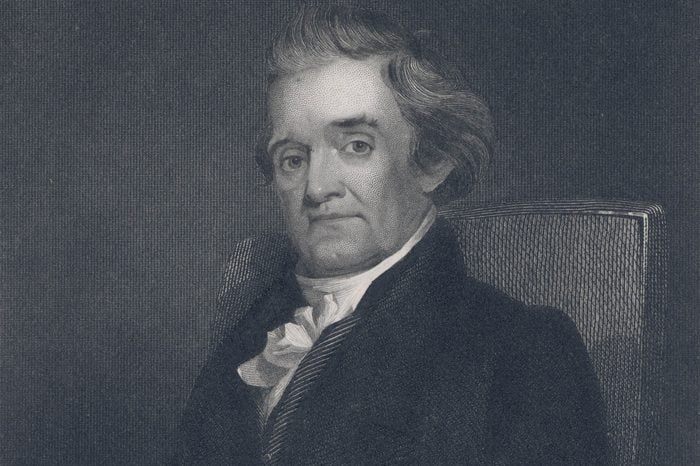

Noah Webster (of dictionary fame) is the reason we have “British vs. American” spellings

“Color” and “colour.” “Program” and “programme.” “Catalog” and “catalogue.” Why do British spellings seem to have these extra letters? Well, shortly after the Revolutionary War, the very pro-independence Noah Webster was adamant that America, officially its own country, should have a distinct way of spelling from the British. It’s the reason Brits and Americans spell “color” differently. He thought many British spellings were overly pedantic and stuffed with superfluous letters. So he wrote an essay in 1789 arguing that Americans were downright treasonous if they weren’t totally on board with spelling reform. Years later, in 1806, he would publish A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, which featured many of the “Americanized” spellings we still use today. However, not all of Webster’s proposed changes became reality. According to Vox, he wanted Americans to spell tongue as “tung”!

Dictionary editors deliberately add fake words

Why would dictionary editors sometimes deliberately include errors? To trap copyright infringers! Though copyright infringers aren’t the only ones they’re toying with—there’s a clever way dictionary editors prank each other. In addition to dictionaries, other resource publications like encyclopedias and maps throw in a fake word (or fact, or place), very much on purpose. If a dictionary (or encyclopedia, or map) from another company, produced later, contains that fake, planted trap, bingo! The “trickers” know that the “trick-ees” were stealing their work, rather than compiling and researching words themselves. In the most famous instance of this, the New Oxford American Dictionary slipped the non-real word “esquivalience” into their 2005 edition. Lo and behold, “esquivalience” appeared, with its fake definition, on dictionary.com. (It’s gone now.)

The least popular letter

The letter that starts the fewest words in English is not particularly surprising: It’s X! It still starts a good 400 words in the current Oxford English Dictionary. But when good old Noah Webster first produced his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, the number of listed words beginning with X was a grand total of…one! (It was, of all things, “xebec,” which describes “a three-masted vessel of the Mediterranean.”)

Sources:

- British Library, “Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabeticall”

- Lexico, “pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis”

- Grammarly, “14 of the Longest Words in English”

- Atlas Obscura, “How the Oxford English Dictionary Went from Murderer’s Pet Project to Internet Lexicon”

- Merriam-Webster, “We Added New Words to the Dictionary for April 2020”

- Philology on the English Language, “Phantomnation”

- Wattpad.com, “A Light in the Attic”

- Dictionary.com, “Is Ironic The Most Abused Word In English?”

- Vox.com, “Why Americans and Brits spell words differently”

- Dictionary.com, “Esquivalience”