The Lessons My Motorcycle—and Grown Daughters—Taught Me on the Road

What one father learned about life, love and the importance of adventure

One sunny Saturday afternoon in 2014, I was southbound on Highway 427 in Toronto, aboard my purple 1993 Harley-Davidson Sportster. This stretch of road, some 12 miles long, is one of the most heavily trafficked in North America. At certain points, there are 14 lanes of traffic, much of it moving at 70-plus mph. I was in one of the center lanes—keeping a close eye on an 18-wheeler about 100 yards ahead.

I wasn’t worried for myself. I’d been biking for decades. My eyes were riveted on my 23-year-old daughter, a novice rider who was balanced on her recently purchased BMW F 650 GS. She was right beside that semi, in its dark shadow, looking as vulnerable as a snowflake.

Thoughts swirled. One wrong move, and our world ends. I am powerless to help her. I let this happen. Am I the worst father ever?

My daughter Ewa Carter, a student at the time, made it home safely and hasn’t stopped riding since. She has put thousands of miles on that BMW, riding from our Toronto home east to Halifax, south to Tennessee and west to Vancouver in all types of weather and road conditions. The best part is that for exactly 5,100 of those miles, I’ve been riding with her.

I’ve had some stunning adventures with Ewa’s identical twin sister, Ria Carter, too. In fact, both my girls have taken me places I never imagined I’d go.

Adventure of a lifetime

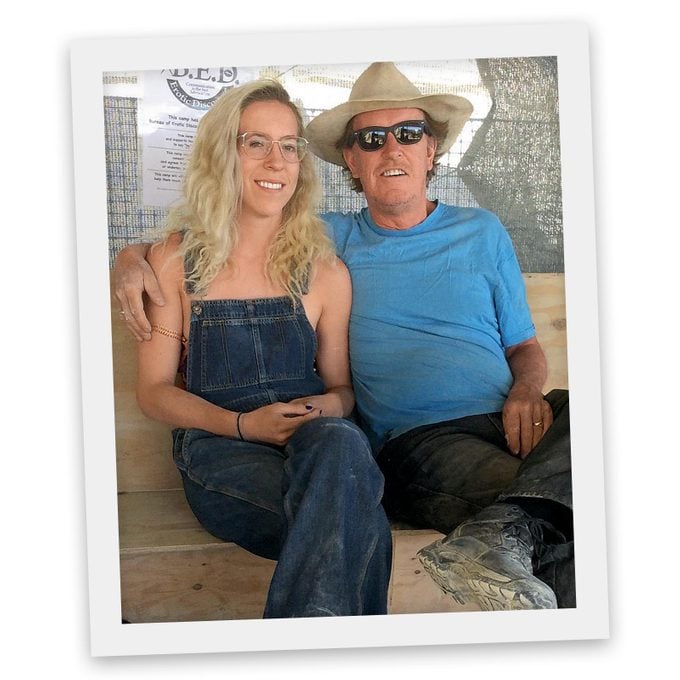

One afternoon in August 2016, Ria, at the time a funeral director and now a psychotherapy student, arrived at our house and told my wife, Helena Szybalski, and me that she was taking me to Burning Man, a festival in the Black Rock Desert in Nevada. Our daughters had attended a few years earlier, frolicking in the heat with 70,000 hippies. And they’d decided, without consulting me, that this was my year to go. Not only had Ria obtained a pair of hard-to-get tickets, she’d also paid our plane fare. If I didn’t go, she’d be out $2,000.

So I said OK. It would be worth being adventurous to find out what my kids knew about their dad that I didn’t.

Burning Man is for adventure-seeking West Coast types—computer whizzes from Silicon Valley, UCLA artists and other outside-the-lines colorers. Why did Ria think I should go? The only drugs I take are Tylenol and hay fever medication. I had been chair of the PTA at my kids’ grade school and a family columnist at a women’s magazine. A female friend in college once pegged me as a churchgoing, 2.5-kids-with-a-minivan-and-picket-fence type of guy. She was absolutely right.

When we arrived in Nevada, it was late and dark; Ria and I soon got separated. The next morning, as I searched for her, one of the first campers to greet me was a slender 30-something woman with long brown hair wearing absolutely nothing. (For the record, I was fully clothed.) She asked what I was looking for, and I said, “My daughter.”

“What you need is a hug,” she said and proceeded to administer one.

“You’ll find your daughter,” she reassured me. I did, a few hours later.

Lessons from my daughters

Burning Man takes place in a temporary city where attendees (called burners) shed normal life and throw a nine-day party that culminates in the burning of a giant wooden statue. Everybody travels around the site on sparklingly decorated bicycles, and the music stops only for a few hours around dawn, when most of the crowd sleeps off the night before. Money rarely changes hands; the only things you can buy are ice and coffee. Otherwise, people share their food, booze and whatever else they have with complete strangers.

You never know what marvel you’ll find around the next corner. One mobile art installation was the fuselage of a full-size decommissioned 747. Imagine a Mad Max setting with pop-up concerts, Cirque du Soleil–caliber gymnastic displays and a 33-foot-tall wooden pirate ship—peopled by a few dozen champagne-swigging burners—moving through the central plaza like a Trojan Horse.

But the most important part? Burning Man was a parenting milestone. Ria tried to give me the experience of a lifetime and succeeded. To this day I can’t stop telling people about it.

On the road together

When it comes to high-proof fathering lessons, though, few adventures compare to the motorcycle road trips I’ve shared with Ewa.

Our first, in August 2017, was a winding trip around the Catskills and Finger Lakes areas of New York. We avoided interstates and spent the week on twisty scenic back roads. At one point, I found myself riding alongside a Catskills meadow not far from Woodstock, keeping pace with a fawn and yelling “Go, Bambi, go!”

On the second day, we stopped in a small town for ice cream. I asked the woman at the picnic table next to us: “What’s the name of this town?”

“Interlaken,” she answered. “Where are you trying to get to?”

Me: “We don’t know.”

It occurred to me then that I’d always wanted to attempt this no-schedule kind of trip, when you ride just for the sake of riding.

Ask any middle-aged motorcyclist: They’ve all fantasized about doing the Easy Rider thing, tossing their wristwatches into a ditch and heading toward the horizon without a plan. Now, traveling with no destination became a trademark of my rides with my daughter.

Since we almost never knew where we were going, we were almost never disappointed when we arrived. Pulling off the highway at the end of each day carried with it exhilaration. The reason to celebrate? We hadn’t crashed!

Because the truth is, life on a motorbike is one close call after another. En route, riders must stay focused 100% of the time. A tiny patch of loose gravel can be fatal. I used to say I found it nerve-racking, but Ewa had a different take: “To me, motorcycling is like meditation.” And I came to realize she was right. At the end of a day of riding, after checking into whatever family-run roadside inn we’d picked, I’d be exhausted but feeling mentally clearer than ever. After a roadhouse meal and a Budweiser or two, sleep was never elusive.

One summer, we toured northern Michigan. That odyssey included a stop to ask directions at the Big Ugly Fish Tavern, whose claim to fame is being the diviest bar in Saginaw. It also involved riding more than a mile with no helmet, which is legal for adults in Michigan, albeit with insurance conditions. While not advisable, it felt as if we were secretly skinny-dipping in a neighbor’s pool. We also biked to a town called Bad Axe simply because it was a town called Bad Axe.

A wild ride

There were a few exceptions to the no-destination rule. On our 2019 trip, after riding for two days, Ewa and I arrived in a town called Deal’s Gap, North Carolina. That’s the starting point of the infamous Tail of the Dragon, a must-ride for any motorcyclist. It’s 11 miles on two narrow lanes with more than 300 curves. Much of one side is a wall of mountain, the other is a sheer drop—with no guardrails. A sign at the beginning of the route reads “Motorcycles: High crash area next 11 miles.”

As if to prove the sign right, about 15 minutes into the route my front wheel hit the dirt beside the pavement. I lost control and drove clumsily down into the shallow grassy ditch, juddering to a stop. Since 55 yards farther on there was no ditch—only a cliff—my “incident” could have been a lot worse. The only thing hurt was my ego.

Had I known how challenging the Tail of the Dragon was going to be, I would not have ridden it. I am a boringly cautious motorcyclist. The Dragon was Ewa’s suggestion, and I am from-the-bottom-of-my-heart grateful that she led me down that path. The route was an absolute thrill ride, and my minor wipeout only added to the excitement.

In August 2020, Ewa moved from Toronto to Vancouver to work as an American Sign Language interpreter. She rode her bike west, and I accompanied her for the first 810 miles along the north shore of Lake Superior. Ewa had been going through a rough time emotionally and wanted to cover the remaining 1,864 miles solo. So right there at the top of the world’s largest freshwater lake, we hugged, and she headed west while I turned east.

A few hours later I hit a tricky part of the highway, steep and coiling, and one section actually had me riding west once again, staring straight into the blinding sunset. I realized through teary eyes that the twists and turns on this stretch pretty much summed up my emotions as I saw my daughter ride off that day.

The next year, 2021, our weeklong bike trip in southern British Columbia coincided with some of the worst forest fires the area had ever seen. I met Ewa in Vancouver, and we headed north on the Sea-to-Sky Highway, past Whistler, past Pemberton, and on to Cache Creek, where we found ourselves between mountains on fire. We had had no idea what we were heading into; the fires had happened so fast. The valleys seemed consumed by flames.

The next day, as we made our way northwest along Highway 16, we saw striking reminders of whose backyard we were biking through: First, a huge brown bear crossed right in front of us, and then, a few miles later, a sleek tan-colored cougar.

A passing of the baton

Three days later we reached Prince Rupert, almost to the top of the province’s coast, and boarded the posh Northern Adventure ferry for a scenic 16-hour cruise to Port Hardy on Vancouver Island.

What made this trip so special was not just that it was the first where we actually had a plan—it was that Ewa took it upon herself to be the planner. We didn’t even have a conversation about it; she just took care of it all. Ewa had not only arranged to borrow from a friend the bike I was riding, she organized the itinerary and even purchased the ferry tickets. She wouldn’t let me pay.

A baton had been passed from one generation to the next. Wordlessly. I did not see that coming.

My old Harley has no gas gauge. When the main gas tank is empty, the bike slows, and you reach down with your left hand and switch to the much smaller auxiliary tank. At that point you have only a few miles’ worth of gas left.

You’d think that after all these years I’d know better than to run out. But there I was, on the first day of one of my annual trips with Ewa, on a lonely stretch of highway leading toward the U.S. border, and my bike sputtered to a stop. There were no homes or businesses in sight.

Ewa was getting smaller as she headed into the distance, not realizing she was riding alone. When she finally saw that I was no longer in her rearview mirror, she turned back. As a father, it’s humbling to be in that position.

Throughout my adult life, in raising my kids I’ve followed my own parents’ lead: I stood aside and offered support while Ewa, Ria and their younger brother, Michel, found their own way in life. I seldom said no.

But when Ewa said she wanted to wait with the out-of-gas bike on the side of the country road while I went for gas, I said no way. I would not leave her vulnerable on the side of a country road for goodness knows how long. She insisted, but I was firm, and Ewa finally gave in and went off in search of gas.

Because no matter how old your kids get, you never stop being a dad.